California Ghost Towns

Boom and Bust: The Fading Legacy of California’s Ghost Towns

California has no shortage of ghost towns. They can be found in every region, tucked away in the landscape or boldly on display as a tourist attraction. A few found at the bottom of manmade lakes can only be seen during a drought year. But where did they come from and where did they go?

California’s early expansion began with the greatest mass migration of people the nation has ever seen. As these early settlers poured into the territory, small towns sprouted up as prolific as the California poppy and the landscape was forever changed. Hopeful prospectors came to find their fortune in gold, farmers came for free land, and others recognized an opportunity to make their fortune in commerce by providing much needed goods and services to these new residents. Folks put down roots, raised families, farmed, and opened businesses, allowing communities to grow and flourish for over a decade. The railroad made its way across the country connecting California to the prosperous east coast and a new way of life was born.

Mining was hard, and many recognized they would never achieve the fortune they hoped for so as new opportunities to earn a living became available, prospectors were swayed away from drudgery of the mining life.

As the mines dried up or became too costly to maintain and hydraulic mining became illegal many of the residents of these small towns opted to move on to bigger cities, or the fertile central valley to farm and raise families. There was no UHaul to help you move, so pioneers often packed what little they could into a wagon and left behind most of their possessions. Eventually, many of these small towns were abandoned or diminished to only a few residents and as such, the Ghost Town was born.

Not all of today’s ghost towns were born from the mining industry. Alcatraz, for instance was once a thriving city with approximately 300 civilians and 275 inmates living on the island but was abandoned in 1963 after 29 years of operation. Hearst Castle, celebrating it’s 100 years, was abruptly abandoned with nearly all the art and possessions intact when the owner was taken ill in the 1940’s. Lastly, Pioneertown wasn’t an actual city, but a western movie set abandoned when an interest in Westerns was replaced with war time sitcoms. These, along with the other towns on our list, provide a unique glimpse into California’s rich history.

Shasta State Historic Park

Six miles west of Redding sits a row of old, half-ruined brick buildings that was formerly the “Queen City” of Northern California’s mining district. Shasta State Historic Park, often referred to as “Old Shasta” by locals, includes ruins along with some nearby roads, cottages, and cemeteries, all of which serve as reminders of the bustling activity that once took place in this former mining town. The County Courthouse has been restored to its original 1862 appearance and serves as a visitor center filled with historic California art. The courtroom, jail, and gallows have also been restored and furnished with many authentic 1860s items to interpret Shasta County’s justice system during the gold rush. The Blumb Bakery was restored so weekend visitors can see 1870s baking styles and techniques in action. The park was unfortunately damaged by the Carr Fire in 2018, during which the elementary school was destroyed, and the brewery and cemetery damaged. Visitors can still enjoy Old Shasta and relive the gold rush era through the artwork on display and events hosted by the Shasta Historical Society, including Holiday in the Park, Shasta Heritage Day, and a reenactment of Joaquin Miller’s experiences living in Northern California during the 1850s, as told in his novel Life Amongst the Modocs.

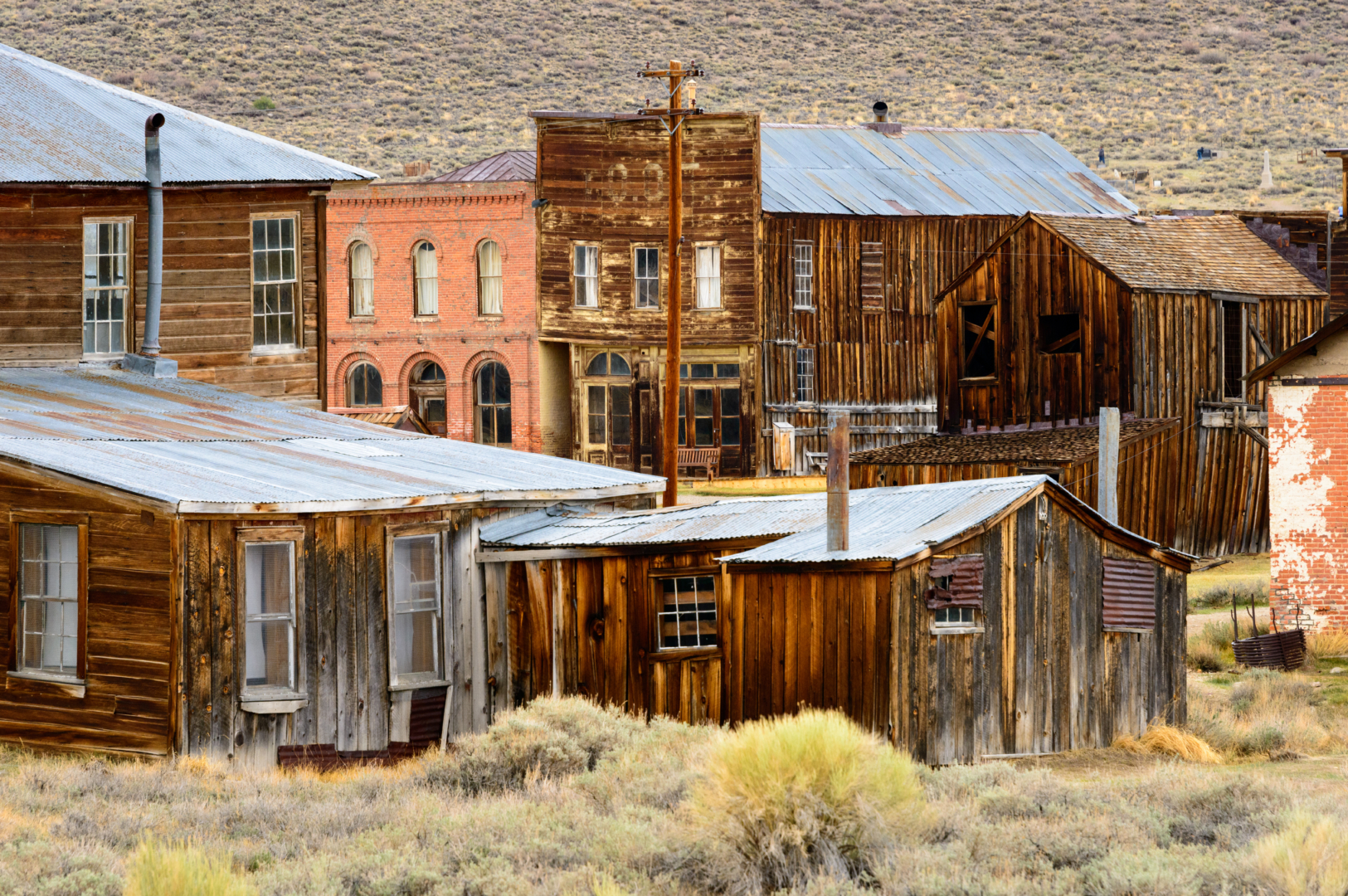

Bodie

Bodie is “a town frozen in time.” During the gold rush boom in the 1880s, the town of Bodie grew to have a population of around 10,000 people. Bustling with families, miners, and store owners, along with robbers, gunfighters, a red-light district, and travelers from all over the world, Bodie was destined to be ridden with crime. There were as many as 65 saloons in town at one point, and they were always filled with miners after their days spent in the mills. The mixture of money, alcohol, and gold would sometimes be deadly. There are reports that the residents would often ask “Have we a man for breakfast?”, which was a polite way of asking if there were any fatal fights the night before. Bodie was more widely known for its lawlessness rather than its riches, and this reputation combined with several fires, Prohibition, and the Great Depression would send Bodie into an irreversible downward spiral. Eventually, the losses from the mines outweighed the gains, and Bodie was finally referred to as a ghost town in 1915. When the Bodie Railway was abandoned and scrapped for iron in 1917, Bodie was almost completely abandoned. There is a story of a little girl whose family was moving from San Francisco to Bodie, and in her diary was written either “Good, by God, I’m going to Bodie” – or – “Goodbye God, I’m going to Bodie”, which perfectly captures the dichotomous reputation of Bodie. Today, visitors can explore Bodie Historic State Park and walk down the deserted streets once filled with people, gold, alcohol, and crime.

Locke

After a fire broke out in the Chinese community of Walnut Grove, the members of that community decided they needed a town of their own and began working with land-owner George Locke to turn their dreams into the eventual town of Locke. George Locke leased the land to the original settlers, because the California Alien Land Law of 1913 prohibited selling farmlands to Asian immigrants; many Chinese immigrants were facing unfair discrimination in bigger cities, so Locke served as a promising venture for people and families trying to solidify their piece of the American Dream. Locke has gone down in history as the nation’s only town completely settled and inhabited by Chinese settlers. Today, Locke’s Chinese population is almost nonexistent, due to many of the original settling families branching out to city suburbs as they received higher education and more progressive views about immigrants were adopted. Locke was designated a National Historic Landmark in 1990 so visitors can appreciate the architecture, history, and hard work that the original Chinese settlers put into this riverside town.

North Bloomfield

In the heart of Gold Country, North Bloomfield takes visitors back 150 years in this preserved gold rush town. Originally named Humbug due to a few failed gold mining trips, the population eventually reached almost 2,000 people once hydraulic mining came into play, which utilizes water to wash away mountainsides in search of gold. As gold mining flourished, the town was renamed North Bloomfield, although this new designation would be short lived. Hydraulic mining was causing countless environmental disasters and was eventually made illegal in 1884. This effectively ended all gold mining efforts in North Bloomfield, causing nearly all miners and their families to abandon their town. Many of the original buildings are still standing today, with some preservation improvements made when necessary. Although not totally abandoned, the small population of less than 10 people are all dedicated to preserving and sharing the history of one of California’s lesser known failed gold rush towns.

Hearst Castle

Although Hearst Castle is not nearly as rustic as some of the other ghost towns in California, it was still abruptly abandoned and would have been forgotten if not for the impressive architecture, art, and history inside its walls. William Randolph Hearst began building “La Cuesta Encantada” (The Enchanted Hill) after he inherited $11 million dollars and the 40,000-acre estate after his mother’s passing. Hearst began putting his fortune into fruition, and from 1920 to 1939, the castle was under construction constantly in an attempt to cater to Hearst’s high-profile guests like Charlie Chaplin and Winston Churchill. When the Great Depression hit along with millions of dollars in debt, Hearst was forced to cease all construction and sell most of his art collection. Hearst’s health was declining, and he left the castle for the last time in May 1947. Luckily, the Hearst Corporation donated Hearst Castle, the gardens, and much of the remaining art to the state of California. Since it was abandoned by its original owner and creator, it has become a major tourist attraction and point of intrigue for many, who are all in awe of the man who built his castle just to abandon it.

Sacramento

When John Sutter arrived on the shore of the American River in 1839 and began establishing Sutter’s Fort, the traffic his fort brought in created the need for commercial businesses, and the City of Sacramento was created. Although Sacramento’s waterfront was an ideal location for success, it was also prone to severe flooding. After several flooding events nearly destroying the entire city, the worst of which being in winter of 1861, effectively turning the Sacramento Valley into an almost 300-mile long inland sea. As many residents left the city for their own safety, others had an idea – raising the streets, buildings, and entire city above the flood level. Thousands of yards of materials were brought in on wagons, and the project to save Sacramento began. As the raising of the city was completed, the old infrastructure created tunnels and corridors underneath the surface of the bustling city. Today, the history of these hardworking settlers can be seen throughout the Old Sacramento Waterfront, a unique 28-acre National Historic Landmark District and State Historic Park that tells the stories of California’s gold rush beginnings. Visitors can experience the California State Railroad Museum (the largest railroad museum in North America with a historical train ride), tour the spooky underground tunnels with the Sacramento History Museum, and take part in “Waterfront Days” on Memorial Day Weekend, featuring Old West theatrics, history reenactments, wagon rides, and more.

Alcatraz Island

Off the coast of San Francisco sits one of the most interesting abandoned communities in Northern California – Alcatraz Island. Like many mining towns in California, Alcatraz’s original purpose was abandoned, and is now a point of fascination for locals and visitors from all over the world. Alcatraz Island was originally meant primarily for a lighthouse, but since has functioned as a military fort, a military prison, and, most famously, Alcatraz Federal Penitentiary. When Alcatraz Island become home to a federal prison in 1934, it was meant to hold the “worst of the worst” – inmates from all over the country who were transferred from other federal prisons for causing problems. Due to its location and the need for maximum security around the clock, Alcatraz was by far the most expensive prison in the country; the expenses coupled with a major escape attempt in 1962 lead to the decision to close the prison in 1963. The infamous inmates combined with attempted escapes, ghost stories, and other rumors surrounding this eerie island has made Alcatraz Island a popular destination for supernatural and historical fans alike. All rumors aside, during its peak, Alcatraz housed an average of 260 inmates along with housing on the island for select staff; inmates and staff also ate all three meals together, every day. Alcatraz sees well over 1 million visitors each year, who can enjoy the chilling stories and rich history of this unique micro-community through tours of the island and main cellhouse.

Julian

Most gold rush activity took place in Northern California, although it wasn’t unheard of for Southern California to experience some of the action. In early 1870, a cattleman found the first fleck of Southern California gold in a creek, creating San Diego’s first and only gold rush. Although Julian was never abandoned, the town’s reason for settling soon changed course. As with the rest of the gold rush towns, when the search for gold was eventually a dead end, few pioneers stayed and began farming the rich land. The farmers quickly discovered Julian to be a perfect place to grow apples, and apples are still grown there to this day; Julian is now widely known for their famous apple pies and their annual Julian Apple Days Festival. Visitors can enjoy a wide variety of year-round activities for families and adults, including their historical museums, horse-drawn carriage rides, wine tasting, apple picking, gold mine tours and gold panning, and more.

Pioneertown

Pioneertown is not like other abandoned mining ghost towns in California’s desert. This scenic, western town was built in 1946 by and for movie industry professionals. Dick Curtis had a dream of a town that could function as a “living breathing movie set” – a place where those in the movie industry could work and play. With cheap land starting at $900/acre, Pioneertown soon became a fully functioning town with a well-established community and big plans for expansion, including a 40-acre lake, a golf course, an airport, and a shopping mall. As the original investors began shifting their money toward other ventures, land sales plummeted; the lack of safe water available to the town and the fact that western films were losing popularity, Pioneertown’s heyday seemed to be finished. Today, Pioneertown welcomes guests to visit to Mane Street (which is accessible by “hoof ‘n’ foot only” – no cars.) Mane Street is the length of a few city blocks and is home to functioning retail shops, false fronts perfect for photos, and even fake gunfights on some summer weekends. Although it is no longer a hotspot for filming movies, Pioneertown is truly “Where the Old West Lives Again”.

Calico

Calico is an Old West mining town located in the beautiful Calico Mountains of the Mojave Desert region of Southern California. In 1881, prospectors discovered silver ore in the dusty mountains near Wall Street Canyon. Soon after, Calico had over 500 mines that reportedly produced more than $20 million in silver ore over a 12-year span. In its prime, Calico was bustling with prospectors and their families during a time when silver was king. The Calico Mining district became one of the richest in the state and could boast boomtown status, producing not only silver, but over $9 million in borax production, and a town with a population of 3,500 that had several saloons, a Chinatown, a schoolhouse and a Red-light district.

Calico was a rip-roaring town teeming with miners, boomers, gamblers and fortune hunters. Thousands of men swarmed up the canyons and gulches from their stone huts each morning to grab with picks and blast with powder the rich silver ore. A dog carried the mail in pouches strapped to his back. The justice of the peace chewed tobacco and swallowed the juice. And the gaudy colors in the minerals stained the mountains which formed a backdrop for it all, reminding someone of a piece of calico fabric. Thus, Calico was named.

Los Angeles Times

When silver lost its value in the mid-1890s, Calico began to lose the majority of its population. Many miners packed up, loaded their mules and moved away, abandoning the town that they once called home. In the blink of an eye, Calico became a ghost of its former self.

This all changed in the 1950s when Walter Knott, the creator of Knott’s Berry Farm, purchased the Calico property. Knott had at one time homesteaded in the Mojave Desert and worked in the Calico mines. He purchased the Calico property with the desire to restore the historic town to a semblance of its former physical glory, which ultimately preserved the historic significance of this era for posterity. Mr. Knott architecturally restored many of the buildings to look as they did in the 1880s. In November of 1966, Mr. Knott donated Calico Ghost Town to the County of San Bernardino to continue the operation of the town as a Regional Park. Calico was designated as State Historical Landmark #782. In 2005, the town was proclaimed by, then Governor Arnold Schwarzenegger, to be California’s Silver Rush Ghost Town.

Today, Calico is part of the San Bernardino County Regional Parks’ system visited by people from around the country and all over the world. In 2018, the Park welcomed over 240,000 visitors. The park offers visitors a glimpse into the past with an opportunity to share in the town’s rich history and enjoy the natural beauty of the surrounding desert landscape. Along with its history, Calico Ghost Town has shops, restaurants, a cemetery, mine and ghost tours, gold panning, a working train, trails overlooking the desert landscape, OHV trails, the Lane House & Museum, and offers camping and outdoor recreation 364 days a year. The park is only closed on Christmas day. Throughout the year, Calico hosts some exciting events including Calico Days celebrating the rich history of the town, Ghost Haunts during the Halloween season, Bluegrass Festival, Civil War re-enactments, and a special Holiday Festival complete with performers, carolers and a tree lighting ceremony. Its campgrounds offer 259 sites as well as a mini bunkhouse that sleeps 6 and a large bunkhouse that sleeps up to 20. Both bunkhouses come complete with bunk beds, electrical, heating and air conditioning. Admission into the town is included with all camping.